I’ve been working on this one for a couple weeks, but wanted to wait for the Fed to confirm. And confirm they have. At the March FOMC press conference, Chairman Jerome Powell summed it up in perhaps the best way he could:

“I don’t know anyone who is confident of their forecast.”

When the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, the most powerful monetary body in the history of the world, essentially admits that they don’t have a handle on events, then you can bet your bottom dollar that nobody does.

So now that that’s been established… just what is going on?

I previously wrote about the state of the pre-2025 economy here.

Since then, the trump administration has announced several rounds of tariffs, detailed below:

– January 26 – 25% tariff on US imports from Colombia over its refusal to accept migrant deportation flights – Revoked

– February 1 – 10% blanket tariff on all US imports from China (est. $450b of goods) – Enacted

– March 4 – Additional 10% blanket tariff on Chinese imports, bringing China tariffs to 20% – Enacted

– March 4 – 25% tariff on global Steel & Aluminum imports to the US (est. $45b of goods) – Enacted

– March 4 – 25% blanket tariff on all US imports from Mexico & Canada (est. $1.3t of goods) – Conditionally Enacted on all goods not covered by USMCA Trade Agreement (est. 38% of total goods in this line item)

– March 4 – 10% tariff on US oil & gas imports from Canada – Delayed until April 2nd

– March 13 – 200% tariff on US alcohol imports from the EU – Delayed

– April 2 – Reciprocal Tariffs on all global US imports, designed to match any perceived additional cost imposed on US exports to other countries – Threat

No one is certain right now of how much will be covered in the April 2nd round of tariffs, but it should cover at least a couple $Trillion in imports. An astounding figure.

And in response, here’s what our new enemies have done in retaliation:

– China has levied 15% tariffs on US farm exports, 15% tariffs on energy exports, and 10% tariffs on agriculture machinery – Enacted

– Canada has levied 25% tariffs on US steel & aluminum exports – Enacted

Before we proceed, we need to understand what tariffs are. There is a reason I wrote out the above application the way I did, because that’s how it works.

A Tariff is a tax on imports. It is an extra level of sales tax that a government levies on an importer when that importer imports. The closest comparable existing tax is a sales tax.

Take the example of a Wine seller, like Total Wine & More. A big part of their inventory is wine that’s produced outside the US. Malbec from Argentina, Champagne from France, and so on. In order to sell that wine to you, Total Wine has to buy it from foreign suppliers in those countries. Levying a tariff on foreign wine would make Total Wine have to pay the government an extra tax in order to import that product.

This is the key point, so I want to make sure you understand it. Tariffs are paid by US Importers. They are NOT paid by exporters outside the US. The purpose of a tariff is to make foreign goods more expensive, but there is no legal authority granted to our government to force foreign companies to pay us money for no reason. There is only legal authority to force domestic companies to pay us money for no reason.

I’m going to issue a more long-form explainer on how tariffs impact consumer activity at a later date, as these massive threats take shape. But for now, just know that the recent announcements have kicked off a whole new business cycle of uncertainty across markets.

Right now, I believe it’s impossible to know the administration’s intentions. It seems that every week features a new sensationally large tariff announcement by trump, followed by members of his cabinet furiously walking it back. As you can see, some have been enacted, and there is reason to believe much more is on its way. And as you can see, trump is more than willing to forget about any accomplishments in his first term, as evidenced by his desire to tear up the USMCA agreement, the NAFTA alternative he himself created, in order to achieve that uncertainty. Perhaps, then, the uncertainty is the goal. But if that’s the case, then we should prepare for the worst.

Speaking of not knowing what the goal is, these actions appear to cater to political whim more than any sort of economic sense.

I’ll be honest with you. I really don’t like reading sentiment surveys. If you’ve read this blog since its inception, you’ll know that I think sentiment surveys are indicators at best, and do not present any real data by which we can shape our knowledge. They are secondary sources of information, that tell us not what people are Doing, but what people are Feeling. And as we all know, thought and feeling does not necessarily mean action.

But moments such as these, the beginning months of a new world of tremendous uncertainty, are what survey data is for, so let’s take a look at how people are feeling.

Every Friday, the University of Michigan releases their Consumer Sentiment surveys that track consumer confidence. It began in 1966 with an index point of 100, and moves up or down depending on sentiment.

Here’s the UMich survey data from the past few years, per WSJ:

Notice the steep drop in 2025. We only have a couple of months to work with, but the consumer is souring on the economy at a rapid rate.

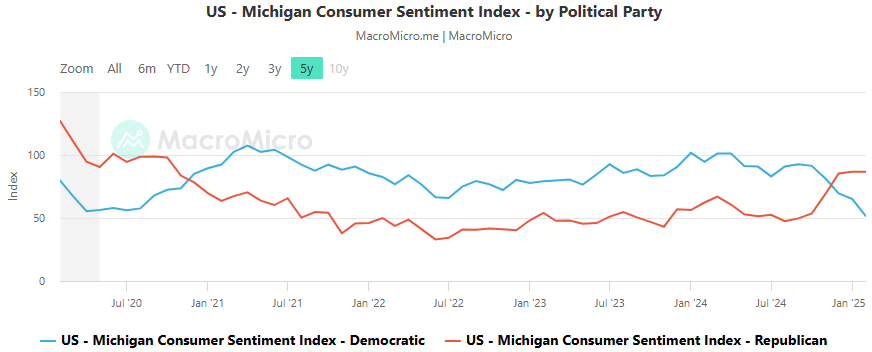

But if we dig a little deeper, it’s not so cut and dry. Here’s the same chart, but broken out by political affiliation:

As you can see, the partisan divide in this country gets more palpable by the year. Democrats and Republicans base their outlook largely by who is in charge of the government, not so much by how the economy actually performs. But unlike previous starts to presidential terms, once the switch happened in Fall 2024, Republicans have not reached that benchmark 100 index point, and remain flat through the first couple of months of the year. Democrats’ outlook, predictably, is plummeting, but the lack of Republican pop suggests a more bipartisan sense of uncertainty.

Finally, how do consumers think inflation will behave in the future? Tariffs, after all, are a government-mandated increase in the price of goods, as clear cut an example of inflation as there can possibly be. Below is consumers’ 1-year future inflation expectation; what level of price increases people expect one year from now.

In just a few short months, people are expecting a comparable level of inflation to the peak of the last cycle, in late 2022. Quite a turnaround from inflation being under control, as it was for most of 2023-24.

Businesses see economic uncertainty and they act by hedging against fluctuation. They will seek currency swaps or repurchase agreements to hedge against currency risk. They will seek discounts to hedge against inventory buildup. There are things they can do to control their downside. But individuals don’t have those tools, nor do they have the fiduciary responsibility to act in a rational manner. When individuals see uncertainty, they get scared, they pull back, and they close their wallets. We have yet to see spending data decrease at the same rate that expectations are decreasing (remember, these measure Feeling, not Doing), but time will tell.

Which brings us to last week’s FOMC meeting.

The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee, or FOMC, meets 8 times per year, holding 2-day meetings to decide their interest rate and other monetary policy. The second meeting of 2025 occurred on March 14-15, where Chair Jerome Powell announced a wait-and-see approach.

Interest rates held at their range of 4.25%-4.5%, while the Balance Sheet runoff was changed. Starting in April, the Fed will continue rolling off its Mortgage-Backed Securities balances, but will slow Treasury roll-off to a crawl, from $25 billion per month to $5 billion.

This suggests that the Fed sees potential weakness in some markets, but overall, as I expressed in a previous issue, the Balance Sheet has rolled off so much that it is now at early 2020 levels, suggesting that all covid-era monetary stimulus is gone, and conditions are much more restrictive now. And before the Fed cuts too much into that lower level, it wants to assess what happens on the fiscal side of things.

As for how it views the current tariff threats, well, the Fed has reason to stay put for now. It draws on experience from trump’s first term, and the trade war that happened back then, and notes that price increases from that trade war were transitory, one-time increases, and were not sustained through multiple rounds of tit-for-tat tariffs and brinksmanship. This is what a transparent, accountable regulatory body does, it draws from experience to better craft a response to the now. Will they be correct this time? Hard to say right now, as real data is yet to come in. But in my opinion, trump 2’s tariff war will not be transitory, the trade flows being targeted are simply too big and our new adversaries have learned from the past as well, to not sit idly by and let themselves be taken advantage of.

The Fed has a predictable rhythm to its actions. It likes to first “talk about talking about” an action, then it talks about the action, then it does the action. The slow nature of monetary policy is designed to ensure transparency with market participants, and also to take into account the feedback from those participants. However, if conditions worsen considerably in a very short time, as they did in March 2020, they can always act rapidly if needed. But right now, they’re staying put.

I’ll have more concrete details regarding tariffs and other news once hard data develops. Right now, this is all largely just conjecture, and the ball is decidedly in trump’s court.

Thanks for reading! I’ve got a few more issues in the works, about different topics that I hope you’ll find interesting. For now, stay tuned!

Discover more from The Millennial Economist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Economics, Economics - Fiscal Policy

how does the level of personal debt affect the outlook?

LikeLike

It can’t be much of a positive contributor, but in recent months, household debt service payments have held flat while the personal savings rate increased. I’d guess that if personal debt levels are on people’s minds, it only makes them more inclined to defer spending.

LikeLike