This topic has been hotly requested, so here we go.

Tariffs! They’re trump’s central economic theme, not a day goes by where they’re not in the news. But even though they’ve suddenly been thrust into the spotlight, I haven’t seen a single long-form explainer on tariffs. What they are, their historical significance, how their use is good or bad, and otherwise more general stuff for the non-economically-inclined public to understand.

Well fear not, dear viewer, because that moment has finally arrived.

What Are Tariffs?

The short answer is, according to Oxford’s Dictionary, “A tax or duty to be paid on a particular class of imports or exports.” They are an additional charge on the price of goods or services, levied by a government, in order to facilitate the collection of money to be spent on services that government provides. Tariffs are taxes, full stop. But they may not be as new of a tax as you think. Let’s look at history.

The creation of the United States of America heralded a new age in human history. Though not the first step on the journey of Enlightenment that began in the late 17th Century, its successful rebellion against colonial empire and creation of a democratic society of self-governance was the catalyst that finally made the Age of Empires begin to recede. After our Declaration of Independence, more revolutions followed, including France and Haiti. Why is this significant in a conversation about tariffs?

Because that historical shift brought with it a commensurate shift in how States see themselves, and how they sustain themselves. The end of the Age of Empires signaled the beginning of the Age of Accountability. Political and Economic systems began to evolve in similar ways, that reflected the State’s accountability to its Population, instead of the other way around. Accountability is the core concept here.

The Enlightenment period brought changes in how humans see the world (science), how humans see each other (politics), and how humans see resources and choices (economics). These areas all evolved together over time to reflect the new societal norm that was being developed, where leaders were elected by the people, accountable to the people, and subject to redress by the people. We will focus on the latter two in this issue.

Politically, power now began to flow from the bottom up, from the people to their leadership, instead of top down, from the leadership to the people. Political inventions like the Vote, the Independent Judiciary, and the Right (to life, liberty, and property) cemented that power. Now, people had a grasp over the kind of countries they lived in, instead of being subjects to rulers of those countries irrespective of their desire to be so.

But economically, things changed just as much. As the people became their own masters, and as their leadership was accountable in actions to them, they also demanded that their leadership be accountable to them in how those actions were paid for. Economies became more complex. Inventions like Fiat Currency (instead of relying on a precious metals standard) and the regulatory institutions that oversee that fiat currency stabilized markets and protected people against cruel swings in prices. Methods of financing government also grew to be more accountable to the people. Older methods of financing government, like demanding tribute from the sovereign’s conquered peoples, grew out of style, and was replaced with the system of Taxation, which tariffs are a part of.

It was all to escape what Thomas Hobbes called the “War of All Against All” and grow to live as a society, cooperating with each other.

The United States and Tariffs

Here in the United States, we have both a Federal and State/Local government, and those two levels of government fund themselves in different ways. Today, we focus on the federal government.

If you ask anybody on the street how they think our government finances itself, they’ll probably tell you they use Income Taxes. And that is largely true. But I’d like you to think bigger than just income taxes.

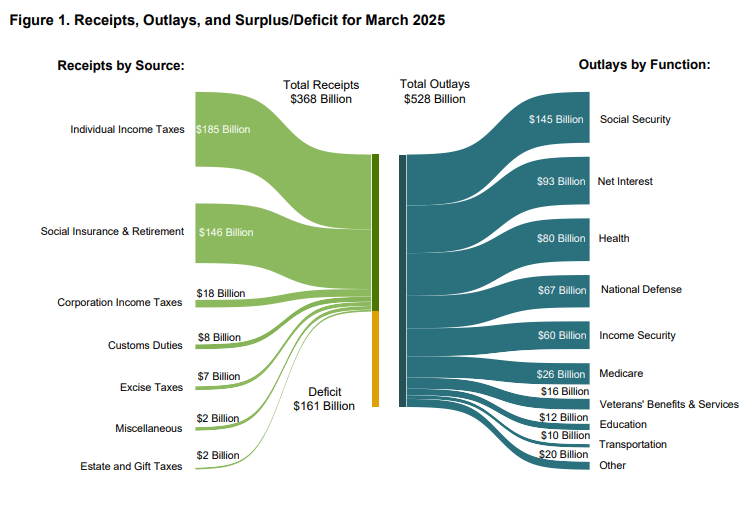

The March 2025 US Treasury monthly financial statement can be found here. It lists the top 6 sources of government funding shown below:

Some categories are taxes on incomes, others are taxes on consumption. But they are all taxes on Transfers. Money is being transferred from one person to another, whether that be from production, consumption, or inheritance. If I work a job and am paid a paycheck, that transfer from my employer to me is subject to tax. If I want to transfer money to my children or grandchildren, then above a certain threshold, that transfer is subject to tax. If I want to buy something, then that transfer of money from me to the store is subject to tax. The Transfer is the important bit.

Just as income taxes are levied on transfers of income, tariffs are taxes levied on transfers of foreign products. The way we mean to use the word Tariff today, means a tax on the transfer of imported goods and services from other countries to America. Any taxes we would levy on goods and services leaving America for other countries, we would call Export Duties. Both are tariffs, in the original sense of the word, and both fall under the “Customs Duties” bucket in the linked March 2025 Treasury Statement.

Within this framework, tariffs are normal. America has actually been levying tariffs for our entire history. Our government has funded itself in three distinct historical eras: First primarily through tariffs, then primarily through excise taxes and Ad Valorem taxes, or taxes on land value, and then finally with income taxes. The first and third are the most pronounced eras, and both rely mainly on taxes on transfers.

I have laid out three graphs below, corresponding to each of the three distinct eras mentioned. The graphs show total US Government Revenue, from 1790 to 2020 broken out by decade, and the amount of that total revenue generated by tariffs and customs duties. Unfortunately, because revenue increases exponentially, putting them all together into one big chart would distort it and not make much sense. Take a look, and then we’ll discuss.

All data can be found on the US Census Bureau’s website, here, and the University of North Texas historical archive, here.

What do we notice?

In the first era, lasting roughly until the Civil War, America funded its government almost entirely from customs duties. We were a frontier nation, primarily focusing on agriculture and manufacturing, and we practiced the American System, designed by such names as Henry Clay, Alexander Hamilton, and John Quincy Adams. One of the tenets of the American System was the establishment of a high general tariff of 20-25% on imported goods. According to the logic of the time, that would provide a shield for nascent American industry, and allow the fledgling country to compete with more established countries. Such revenue would be expended on improving the country’s infrastructure, and to pay off the national debt, at the time a brand new thing (!), overseen by the newly chartered Second Bank of the United States. Budgets were balanced, and America grew rapidly into industrialization.

This might sound nice, but there’s a catch. The Capitalist Urge to Excess knows no bounds, not even with raising taxes. The country became so reliant on tariffs that beginning in 1816, tariffs became steadily higher and higher, culminating in the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations” that plunged the country into a Panic (the era’s recession) and threatened a civil war between North and South. Because the two sides’ economies were so different, the South specializing in agriculture and the North specializing in manufacturing, the economic incentives became opposite between them. Northern states wanted higher tariffs to ensure American raw materials could be used for American manufacturing, while Southern states, with more capital-intensive economies, needed foreign imports to sustain themselves. When the Northern side won the day and the tariff was passed, the South threatened to secede.

Tariff-led trade policy would continue to be a driver toward the many Panics that gripped America during that time, including those in 1802, 1807, 1828, 1836, 1839, and 1857.

Eventually, America came to face the fact that consumption taxes were not the most efficient form of funding a government that spans from sea to shining sea. Ours is a huge country, with massive variation in industry, population, and culture; what’s good for the goose is not necessarily good for the gander. Also, the world was rapidly changing! Global industrialization led to industrial wars, and global trade policies. The American State started to grow into other areas that sought to promote the general welfare; things like land conservation, institutional protection for things like intellectual property, and more efficient forms of educating our youth. The size and scope of society grew, so the State had to grow with it. And that meant we couldn’t rely on solely customs duties to fund it all.

Another form of raising revenue was needed. One that didn’t punish one segment of the population to benefit another, but instead would punish the whole population equally, sharing a common burden towards a common goal. We furthered the Age of Accountability by moving toward utilization of taxes that more equitably shared the burden of governance by all people.

The progressive income tax was first implemented during the Civil War, and was signed into law in 1913, when Congress ratified the 16th Amendment. You can see the clear shift in the data starting in 1920, as customs duties stopped being our main source of federal revenue, and the income tax took over. What initially began as a 1% tax on incomes above $3,000 (a large amount back in 1913!) eventually expanded both ways; the tax rate went higher with incomes, and eventually all Americans became subject to the tax. But the idea stayed the same; All Americans would be taxed on the one thing they all (ideally) had in common, their incomes, and the higher the income, the greater the ability to pay the tax, so the heavier the levy would fall. Tax rates would rise and fall through the decades, famously reaching a top marginal rate of 94% in 1944 on incomes above $200,000, before falling to the current top marginal rate of 37% on incomes above $626,350.

Tariffs never went away. Our tariff rates have gone up and down over time, from the aforementioned general 20-25% rate in 1816, down to the pre-2017 tariff level of about 2%. What is happening in 2025 is truly an anomaly, a freak event never before seen in our history in both its scope and its speed. But tariffs, in some form, have always existed in America, and will likely continue to always exist. Why is that?

It’s because there will always be political reasons for utilizing tariffs. For better or for worse, they are a tool by which domestic industry can be strengthened. There will always be a political incentive to boost a specific domestic industry, or set of industries. Maybe one president wants to grow domestic renewable energy generators and solar panel makers, so he’ll create legislation that raises the costs of foreign-made solar panels. Maybe the next president wants to do the same with semiconductors. Maybe we’re living through this right now. Political Economy is key, the two interplay off each other.

Here’s an interesting little story. Ever wonder why Manila Folders got their name? Because in the 1830s, after the Tariff of Abominations mentioned above, we lost so many of our foreign paper supply chains and paper products, that we needed to source domestic replacements. When this wasn’t possible, we turned to the Philippines, at the time an American colony, and used its hemp imports to create folders and envelopes imported from the Philippine capital of Manila. Imports from colonies were tariff-free. Their tougher, thicker paper stock had a distinct feel, and to this day, we know them as Manila Folders and Envelopes. An example of tariffs being applied for political reasons, and morphing into their own distinct product mix that’s still used today.

But the philosophical argument goes deeper than the political one. The decision whether to base government revenues off of tariffs or income taxes, ultimately is a decision on who carries the burden of funding the State. With tariffs, foreigners carry that burden, and with income taxes, the domestic citizenry carries it. Think of it like a spectrum, and think of America traveling slowly from one side to the other. This is the story of our development, from a newborn nation with no economic power, to the greatest economy in the history of the world. We no longer need to rely on foreigners to prop up our entire state, irrespective of whether they even can anymore. It’s a stepping stone, one to be outgrown as your society grows. We grew out of it.

Tariffs In Practice

Tariffs have indeed been a part of American economic policy since our founding, but now let’s get into the nitty gritty. Beyond the simple definition, how do they work? When a country levies tariffs, what exactly happens? I will endeavor to be as detailed as practically possible, while not mentioning every detail of how the economics works, but including second-order effects beyond just the levying of the tariff.

We’ll focus on one industry, with a truly global focus where lots of different countries have competed with each other for thousands of years: Wine and Alcoholic Beverages. America has a competitive alcohol industry, where different regions of the country produce different drinks that are consumed by Americans and exported to global markets. Kentucky is the birthplace of Bourbon, Napa Valley specializes in dry, fruity Cabernets, and so on. We have our areas of expertise, as David Ricardo put it, our Comparative Advantage. But by no means are we the entire market. Slavic countries have perfected Vodka, the French specialize in sweeter Wines and Champagnes, the Japanese have Sake, and so on. The alcohol industry is a truly global one. American alcohol sellers, such as Total Wine & More, do a lot of importing foreign brands to sell to Americans, on top of the domestic product they sell. Total Wine is a retailer that sells it all, and we’ll be using them as our subject.

Total Wine sells a Courtney Benham Cabernet Sauvignon from Sonoma, California here for $24.99. It also sells a French Chateau Limothe Bordeaux here for $12.99. Finally, it sells an Argentinian Altaland Malbec from Mendoza here for $19.99. To try and stay consistent, I’ve selected three lower-priced bottles, each from their respective 2022 collections, and each playing to their respective regions’ strengths.

Now let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that there is a good political reason to want American winemaking to grow in market share relative to its global competitors. Maybe climate change has made some regions too hot to grow grapes, or maybe the Great Wine Wars have kicked off in another country, whose treasury authorizes purchases of the majority of another country’s winemakers’ stocks. Whatever the reason, America now has an interest in protecting its own industry, and the chosen strategy for doing that is by levying a tariff. President Whine (not punny at all…) decides to put up a 100% tariff on foreign wines, in order to make the more expensive American brand more competitive to American consumers.

Total Wine, as a seller of imported foreign wines, normally has a multi-step process before those foreign wines get sold. They first have to contract with a foreign supplier, in this example that would be the Altaland and Chateau Limothe companies in Argentina and France, respectively. Total Wine agrees to buy wine from those suppliers at a mutually agreed-upon price, and once the product is shipped to America, it then turns around and sells the product to American consumers, usually for more than they purchased it for, profiting the difference as mark-up. But now that tariffs have been introduced into the equation, the process works a bit differently.

With the tariff in place, Total Wine still agrees on a price with its foreign supplier, and can still import foreign wine. But upon that wine arriving in the US, at a Port of Call or similar terminal, the US Customs Office charges the 100% tariff to Total Wine, for the privilege of importing the product. If Total Wine buys bottles of Argentinian Malbec for $15, and sells them for $19.99, it profits about $5 per bottle. With the tariff, however, it still buys bottles from Argentina for $15, but it now has to pay an extra $15 to the US Customs Office. The Argentinian supplier still receives only $15, but Total Wine’s cost is now $30, and in order to make any money off these bottles, it must sell them for higher than $30. The Argentinian company pays nothing, the US importer pays everything. This is why tariffs are taxes on imports.

But Total Wine is big business, and it didn’t get to be big business by allowing its margins to collapse. Before the tariff was implemented, it enjoyed a 25% margin on sales of the Argentinian wine, buying for $15 and selling for $19.99 for a $4.99 profit. Now, it has to pay $30 for the same bottle, but it still wants that 25% margin, if it can keep it. So the new price that it wants to sell the bottle for is $37.50, because $7.50 is 25% of $30.

Will its customers pay that higher price? The 100% tariff has pushed the price of that bottle up from $15.99 to a high of $37.50, so the 100% tariff actually has the potential to increase consumer costs by 87.5%. But if I’m someone who likes his Malbec (it’s actually my favorite red wine), I’m not going to accept a near doubling of my favorite bottle overnight. Total Wine is aware of the decrease in consumption that would follow such an increase, so it will decide how much, and in what manner, it wants to pass through that additional cost to me, the consumer. It may want to space out the increase, making it so the bottle gets 10% more expensive every couple of months before finally arriving at the higher price. It may never get to that higher price because sales decrease so much. But Total Wine understands that every day it does not raise the price to meet its original margin, is a day where it loses potential profits, so it has a vested interest in making this decision quickly. Reality is more complicated than the simple math, and this is a perfect example.

But let’s keep it simple, using the math above for both foreign bottles. Let’s say that in addition to the Argentinian wine, Total Wine purchases the French wine for $9, and by selling it for $12.99, they enjoy a $3.99 margin, or 44%. After the 100% tariff on foreign wine is levied. now the American wine still costs $24.99, but the French bottle now costs $25.92, and the Argentinian bottle now costs $37.50. All of a sudden, the American bottle is cheaper than its foreign competitors, and if the American consumer wants to buy a bottle of wine, it makes more sense to buy American. Sounds pretty good!

The catch always comes on the back end. This is a double-edged sword, and we would be wise to acknowledge what’s actually just happened. The average price for a bottle of wine, of the three bottles, used to be $19.32 (add up the three costs and divide by three), but now, the average price has been raised to $29.47, an average increase of nearly 53%! There will indeed be a segment of Total Wine’s customers that switch to purchasing the American bottle and keep their quantity of bottles purchased the same. But we would be foolish to expect that out of everybody. There will always be, what economists call, “Scarring at the margins,” customers taking their limited dollars elsewhere, and buying other products. People won’t magically be making 53% more money to spend on wine, for the most part, their budgets will remain the same. All that’s changed is prices have gone up, and that means people won’t be able to buy the same quantity of products with their same quantity of dollars. People will react in various ways.

Some people, will keep doing what they’re doing. Others, as mentioned, will make the switch to buy American and keep buying the same quantity. But others will not. Some will switch to lower-cost alternatives, like beer or even water. Others will boycott, refusing to buy any wine until the price comes back down. But at any rate, a new equilibrium point will have to be reached.

Econ 101 teaches us how to plot the graph of Supply and Demand. The most basic graph that shows this is pictured below.

The simple graph actually has four components; Supply (the red line), Demand (the blue line), the Price (the Y axis) and the Quantity (the X axis). Two things are happening here. As the quantity of goods goes up, supply also goes up, and also their price. This is because producers want to earn as much money as they can for the products they produce and sell. But as quantity goes up, demand goes down, leading to the price going down. This is because consumers will want to buy less of a product if it’s ubiquitous, expensive, and not special anymore. The equilibrium point, where these two forces meet, is the point that the price and quantity meet; the point that’s acceptable for both the people selling the product, and the people buying the product. That is the price you see in the store.

But what happens to this graph when a tariff is introduced? A tariff is an adjustment to the price. That equilibrium point goes up, and ends up at a higher point on the graph than it meets normally. In our wine example, the average price went up by about 40%. The new graph looks something like this:

The price has moved up the graph, resulting in a new starting point for the supply line. Producers still want to produce, import, and sell products, and as we’ve seen above, they now must do that at higher prices, But a new demand line does not form. The government did not give the consumer more money, consumers still must make do with the money they’ve got. So the increased price with the tariff means lower demand for the product. Our new equilibrium point is now further back on both supply and demand curves. Suppliers no longer need to supply the same quantity of product to achieve the same level of profit, and consumers cannot afford the same quantity of product.

What we’re left with, in addition to the new equilibrium price, is that shaded triangle at the center, aptly labeled Deadweight Loss. Deadweight loss is the loss of measurable economic benefit, shared by both producers and consumers, as a result of the price increase. Both sides are now making do with less, and both sides have lost out. The additional cost of the products consumers buy, the burden they must bear, is now that much heavier. That additional heft, is dead weight.

Reducing dead weight is what focusing on free markets is all about. In a perfect world, where producers and consumers interact in a perfectly efficient manner, there is no deadweight loss, because there is nothing extraordinary impeding the two sides from reaching their equilibrium price. A tariff is such an extraordinary factor. A barrier, put up to separate the domestic consumer from the foreign product, but whose price is paid by the domestic country.

The economics show that levying tariffs leads to lower economic activity in the long run. They are a political tool in an economic world, a form of government intervention meant to win a kind of pyrrhic victory. If you make the economy a battlefield, you can pull out a victory, but there will always be damage. In the battlefield of trade, tariffs are meant to pull out a political victory.

In our wine example, total wine consumption will decrease if the tariff is levied. But, a greater portion of that lesser total consumption will be American wine. That is the political win. It’s a gamble! And leadership has to have a certain amount of bravery to take that gamble. The gamble doesn’t always pay off. But it can still lead to good outcomes. The Dismal Science of Economics revolves around incentives and relativity, not facts and objectivity, and if the economic reality changes enough, what was once viewed as a loss can instead be viewed as a win.

But keep your level head, and don’t let yourself be fooled.

Conclusion

At no point in this Big Tariff Explainer did I try to make it political. I will save the political side of this discussion for another time. This explainer is simply to inform how tariffs work, why they are used, and what our history is with them. What trump wants to get out of them, is not pertinent today. I hope I have been successful in this regard, and I hope that you can continue to consult this explainer throughout our journey.

Societal development is a journey. One with a start point, and also an end point. Humanity has been on this journey for thousands of years, our history is emblematic of our struggle for a better society. Tariffs represent a mid-point on the economic side of that journey; a mix between imperial ambition and democratic burden-sharing. Tariffs have their place on the scale, and are still a tool in policymakers’ toolbox. Ultimately, their place in history will be tied to how humanity continues to evolve. Will we continue our journey into the just society we envision? Time will tell.

All sources cited here:

1. March US Treasury Monthly Statement: https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/mts/mts0325.pdf

2. US Census Bureau Historical Data 1791-1945: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1949/compendia/hist_stats_1789-1945/hist_stats_1789-1945-chP.pdf

3. University of North Texas Digital Library, Government Documents: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc815472/m1/5/

4. IRS 2025 Income Tax Brackets: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-releases-tax-inflation-adjustments-for-tax-year-2025

5. Total Wine & More Pricing: https://www.totalwine.com/wine/red-wine/malbec/altaland-malbec-mendoza-by-catena-family-wines/p/239112750?s=905&igrules=true

6. Graphs created by myself or taken from Google Images.

Discover more from The Millennial Economist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Uncategorized

In the wine example. Instead of raising the foreign prices to higher than american, the store may raise the prices just a bit, and also the American price a bit too, evening out the increases, so not as much business is lost. Then there will be less incentive to buy american, voiding the purpose of the tariff

Yahoo Mail: Search, Organize, Conquer

LikeLike